General anaesthesia is a vital aspect of veterinary medicine that is never taken lightly, as it demands as much care and expertise as the surgery it is being used for.

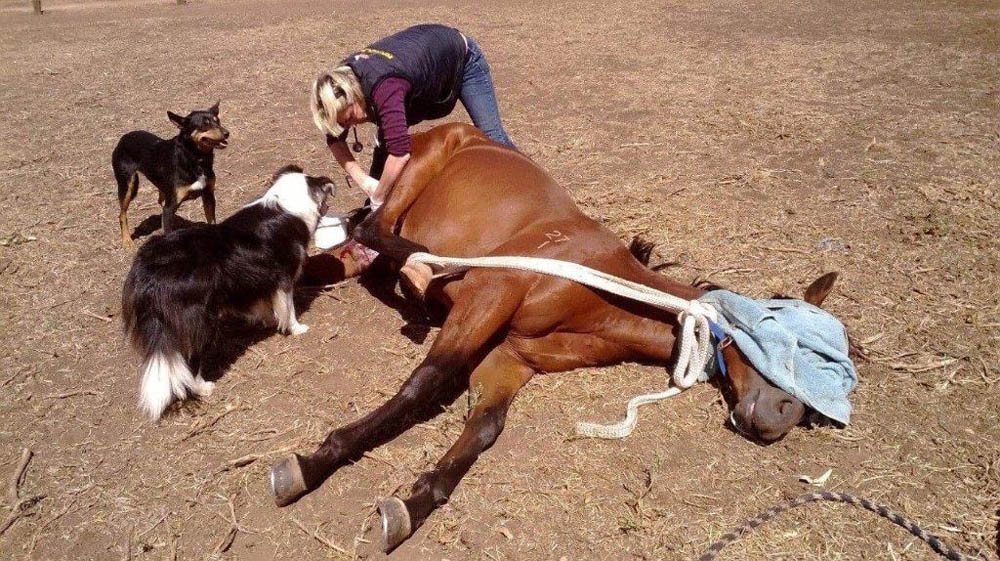

Anaesthetising a horse is not a new procedure and many owners, at some time during their life, would have seen or had the need to have had a horse anaesthetised. General anaesthesia is commonly performed for castrations and stitch-ups in the field and done routinely for many orthopaedic surgeries at equine hospitals.

Frequently, a general anaesthesia is performed for emergency situations such as surgical colics and caesareans. However, it is not a procedure that can be performed lightly or without risk, even though it is often seen as only an adjunct to the more important surgery. Anaesthesia requires equally as much expertise and knowledge as the surgery it is being performed for requires. Despite all precautions taken before and during an anaesthesia, deaths can and do occur, even during the simplest of procedures.

The anaesthesia procedure is divided into three parts, each with a smooth transition from one part of the procedure into the other. These are:

- INDUCTION OF ANAESTHESIA

- MAINTENANCE OF ANAESTHESIA

- RECOVERY FROM ANAESTHESIA

Horses generally require intravenous administration of medication to induce anaesthesia due to their size and the need for a smooth induction. Foals have had a masked applied over the mouth and nose in the past using a gaseous agent to induce the anaesthesia, but this is not practical in a large animal.

There are a variety of protocols and medications that have been used to “knock a horse out”, but most anaesthesia given in recent times are based on a two-part procedure using an alpha-2 agonist such as xylazine to heavily sedate the horse, followed by a drug called ketamine that induces the anaesthesia. There are multiple small adaptions that can be made to this protocol, and these will usually vary depending on the veterinarian’s personal preference. Acepromazine is sometimes used as a pre-med sedative and given within the preceding hour before surgery. A muscle relaxant such as diazepam (Valium), midazolam or guaifenesin can be given with or shortly before the ketamine, so the horse relaxes and sinks to the ground gently.

I would commonly use diazepam with my ketamine administration as I find the horses are induced more smoothly than with ketamine alone. Guaifenesin, or “GG” as it is also known, is not used as commonly as diazepam to induce muscle relaxation, as the GG requires large doses (200-300ml) be given via a drip system, and this can be awkward in horses that try to walk forward and stagger while the drug is being administered. GG also acts as an irritant if it is administered outside of the vein, so a catheter should be placed when using this drug to minimise the risk of it being injected peri-vascularly if the horse moves around excessively or is difficult to inject due to temperament. A combination of an alpha-2 agonist, ketamine, and guaifenesin, colloquially known as “triple drip” can also be used to induce anaesthesia but is more commonly used as a method of maintaining the anaesthesia.

INTRAVENOUS OR GASEOUS

There are two major ways to maintain anaesthesia in the horse — by intravenous medications or by gaseous inhalation. For field anaesthesia, or short-term anaesthesia performed in paddocks or stables, either the initial induction dose is sufficient to complete the procedure or incremental doses of ketamine and/or diazepam, and/or xylazine are given throughout the procedure to maintain a surgical plane of anaesthesia. Ideally, field anaesthesia should not be used if the procedure is expected to be over 60 minutes long, as this can compromise the health of the horse. Some vets will use the triple drip mentioned above to maintain a steady slow infusion of medication to maintain the anaesthetised horse.

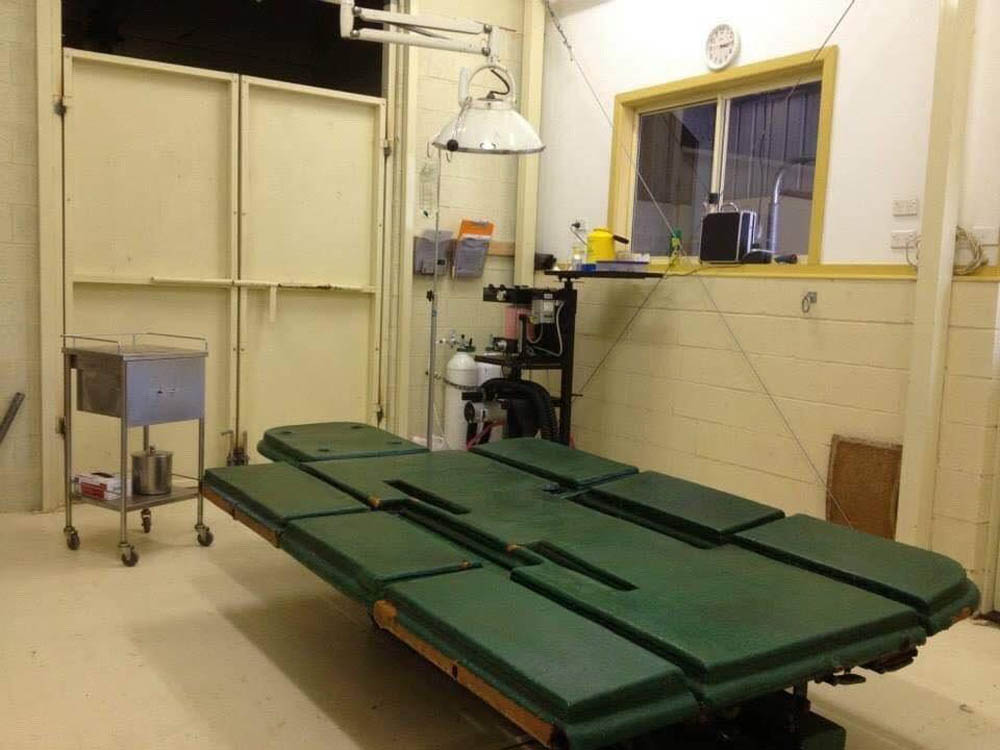

If a procedure is expected to be a prolonged event, then referral to a hospital facility where a gas anaesthetic machine can be used is preferred. There are several gas anaesthesia drugs that can be used, with isoflurane and sevoflurane being the main ones here in Australia. Halothane was commonly used in the late 20th century, but its safety margin and its predictability are not as good as the newer gases and, as such, it is slowly fading out of use.

The recovery phase from the anaesthesia is potentially the riskier part to the procedure as horses recover at different rates, and some horses, particularly highly-strung horses, attempt to rise before they are ready to maintain themselves in a standing position. Ideally, a horse will sit up in sternal recumbency (sit up on their chest with their legs tucked in underneath) and after several minutes like this, extend their two front legs out in front and lift the front half of their body up and attempt to get their hind legs in underneath them to support the rest of their body. If not ready to stand, the horse will get up on its forelimbs and then stumble over, fall backwards, or get part way up and go back down if their hindlimbs won’t support them. Some veterinarians prefer to assist horses in recovery and use a rope on the head and on the tail to manually pull on and help the horse stand as well as balance once standing.

Anaesthetics used predominantly pre-1980s resulted in a lot of terrible recoveries, as the horses were more ataxic and less relaxed when waking and this caused a higher rate of injury (predominantly fractured limbs), than the newer drugs currently in use. Horses subjected to prolonged periods of anaesthesia are more at risk of a bad recovery than those horses given a short anaesthesia.

There is a large array of medical equipment available that monitors respiration, heart rate, blood pressure and oxygen/carbon dioxide levels to allow the anaesthetist to maintain the horse in a good surgical plane of anaesthesia in the safest possible manner. Most of this equipment is available in large hospital facilities but seldom used in short field anaesthesia.

COMPLICATIONS

There are several complications that can occur during anaesthesia and whilst they can be minimised with good protocols in place, they cannot be eliminated. The risk of a horse breaking a leg during induction or recovery has been mentioned above, while other complications seen include myositis (an inflammation or swelling of the muscles), neuropathy (nerve damage causing numbness and loss of use of the structures innovated by the nerve) and sudden death due to an adverse reaction to one of the medications used.

Horses are at an increased risk of developing myositis and neuropathies when they lie in the one position for an extended period and pressure is focused on a small area throughout this time. For this reason, large, padded cushions or tyres are used between the horse and the static structure they are lying on or against (usually the surgery table). Often the anaesthetist will intermittently passively move a limb up and down or back and forward to encourage blood flow and reduce the time an area of muscle is maintained in the exact same position. This is important for any anaesthesia that goes on for more than an hour. It is also important with an extended anaesthesia that the horse is maintained on an intravenous fluid drip and its blood pressure is monitored constantly, as low blood pressure increases the risk of anaesthetic complications because of poor blood flow. Medications are available to improve blood pressure if the blood pressure drops to a low level and can’t be improved by intravenous fluids alone.

Neuropathies can be seen when pressure is focused on part of a nerve for an extended time and result in the nerve not functioning properly for hours to days after the procedure. It can also occur when limbs are placed in an overextended position or an “unnatural” position for a prolonged period, causing the affected nerve to be stretched or compromised. One of the more commonly seen neuropathies is a facial paralysis that occurs when the horse is left in lateral recumbency (lying on his side) with a buckle from the head collar pushed into the face on the underside of the head. When the horse wakes up, the muzzle is seen to deviate away from the affected side and the alar fold inside the affected nostril is flaccid.

Another neuropathy seen post-anaesthesia in horses is a radial nerve neuropathy due to pressure on the shoulder region when the horse is in lateral recumbency. Paralysis of the radial nerve gives a characteristic appearance of a dropped elbow with the front of the hoof resting on the ground, as the horse is unable to flex the shoulder, extend the limb or weight-bear. The incidence of these neuropathies is reduced by taking precautionary measures such as removing the head collar or pulling the lower limb forward when the horse is in lateral recumbency for an anticipated prolonged anaesthesia.

One rare but fatal complication involving damage to the nerves is known as Spinal Cord Malacia and is a result of poor oxygenation and blood flow to the spinal cord. Affected horses are unable to stand after the anaesthesia as they have no function in their hind end and at best can only sit up in a dog sitting position. Spinal Cord Malacia was seen more in young, heavy Shire breeds and was associated with the use of the gaseous agent halothane, which fortunately is seldom used now.

“The risks can be greatly reduced.”

VENTILATION

Horses require good ventilation when anaesthetised to clear the carbon dioxide produced and supply oxygen to cells. This is not a major concern in short procedures but is extremely important in horses anaesthetised for long periods. In many larger referral hospitals, ventilators are used to physically breathe for the horse during anaesthesia. If there is no ventilator available, the anaesthetist may need to manually breathe for the horse using a rebreathing bag attached to the anaesthetic machine if the horse is not breathing adequately alone.

In my experience, large, fit racehorses can be some of the more difficult patients to anaesthetise as they may only breathe once a minute and don’t always take in enough anaesthesia to maintain them in a steady plane of anaesthesia. In these cases, the horse can be artificially ventilated either using a ventilator or a rebreathing bag, until they achieve a steady and regular breathing pattern on their own.

Extra care needs to be taken for procedures that require the horse to be turned over from one side to the other during surgery, as the lower lung (when laying in lateral recumbency) becomes heavy with fluid and less oxygenated. If the horse is turned over too quickly this heavier lung lobe becomes the upper lung lobe and can compress the lower lobe due to its increased weight and compromise the amount of air that can be inhaled. By holding the horse in dorsal recumbency (on its back) until it takes a good breath, the risk of respiratory compromise is reduced as it allows the heavy lung to become better aerated and reduces the pressure placed on the other lung lobe when turned over.

MINIMISING THE RISKS

Can we eliminate the risk of a horse dying under anaesthesia?

The best we can do is minimise the risks and we can do this by being adequately prepared before the horse is anesthetised. Whilst this may not always be feasible in cases of an emergency, as much preparation that can be done prior to induction to maximise the safety of the horse, should be done. In field anaesthesia, this involves checking the environment in which the horse is to be induced, ensuring adequate room for the horse to lie down in, allowing for movement of the horse during the induction and space to recover and stand without the danger of obstacles to stumble onto or into. Keeping the animal as quiet as possible prior to the anaesthesia is important, as highly strung and excitable horses are much harder to anaesthetise due to the adrenaline circulating through their body. Try and keep noise levels to a minimum during induction and recovery as a horse reacts to a threat with a flight response and sudden loud noises can cause the release of adrenaline resulting in the horse trying to move when not fully anaesthetised.

Except in emergency situations, horses should be well hydrated and not suffering with infections or injuries that compromise their ability to go down or get up readily. If there are injuries that require anaesthesia, then adequate thought should be given into how the horse will be treated and prepared to enable the safest induction and recovery. This may require employing extra people and equipment to help the horse stand on recovery, rather than allowing the horse to get up on its own. Using pulleys and ropes to assist the horse to recovery is fine, provided everything is planned carefully and prepared prior to the horse being induced.

For emergency surgeries where time is crucial, the administration of intravenous fluids can begin while the horse is being prepared for the anaesthesia and can continue throughout the surgery to improve the quality of the anaesthesia. The use of appropriate pain relief pre-surgery and, if necessary, during surgery can also have a positive effect on the quality of the anaesthesia and the recovery. Extremely fit horses often make better candidates for surgery if allowed to “let down” for a couple of days or weeks prior to the anaesthesia — so delaying surgery for a short period to allow this to happen can be beneficial provided the surgery is elective.

In summary, anaesthetising a horse is not something to be taken lightly, but nor is it something to shy away from. It is a vital part of veterinary medicine, and provided adequate care and forethought are given to the procedure before the horse is anaesthetised, the risks can be greatly reduced. Unfortunately, the risks can never be eliminated as even with the best of care and planning by experts there is an inherent risk of death or severe complications, and if these occur it is devastating for everyone. EQ

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE TO READ THE FOLLOWING BY DR MAXINE BRAIN:

A Quick Guide to Castration – Equestrian Life, November, 2021

Caring for Mammary Glands – Equestrian Life, October, 2021

Sepsis In Foals – Equestrian Life, September 2021

Understanding Tendon Sheath Inflammation – Equestrian Life, August 2021

The Mystery of Equine Shivers – Equestrian Life, July 2021

Heads up for the Big Chill – Equestrian Life, June 2021

The Ridden Horse Pain Ethogram – Equestrian Life, May 2021

The Benefits of Genetic Testing – Equestrian Life, April 2021

Heavy Metal Toxicities – Equestrian Life, March 2021

Euthanasia, the Toughest Decision – Equestrian Life, February 2021

How to Beat Heat Stress – Equestrian Life, January 2021

Medicinal Cannabis for Horses – Equestrian Life, December 2020

Foal Diarrhoea Part 2: Infectious Diarrhoea – Equestrian Life, November 2020

Foal Diarrhoea (Don’t Panic!) – Equestrian Life, October 2020

Urticaria Calls For Detective Work – Equestrian Life, September 2020

Winter’s Scourge, The Foot Abscess – Equestrian Life, August 2020

Core Strengthening & Balance Exercises – Equestrian Life, July 2020

The Principles of Rehabilitation – Equestrian Life, June 2020

When is Old, Too Old? – Equestrian Life, May 2020