Horses are unpredictable creatures, and it is ingrained in their DNA to escape danger. While this is theoretically easy for us to understand, it is a harder to appreciate when your horse has just disappeared out from underneath you and is halfway across the arena because a leaf moved.

“The horse is a flight animal

– its main defence is to run away.”

While there is somewhat of a language barrier between you and your horse, we can understand their inner thoughts a little better by applying the Polyvagal Theory. We are all familiar with the survival strategies of Fight, Flight, and Freeze. I have written about these stress responses both about stress in horses and stress and anxiety in riders, and why understanding these automatic stress responses helps us perform better, as well as helping us train our horses more effectively.

Briefly, horses and humans both have a nervous system that is wired so that if we are stressed, we can automatically, instinctively and virtually instantly fine-tune our physiology so we can respond efficiently to stress. The Sympathetic Nervous System is like an accelerator that helps us fight or flee. It causes adrenaline to surge through our veins resulting in an increased heart rate, respiratory rate, and muscle tone all to heighten our chances of survival.

We know that the horse, as a prey animal, will generally prefer to run away from things that frighten it. They are a flight animal, and their main defence is to put as much distance between them and the threat. A horse in an unfamiliar environment is likely to be vigilant and easily startled. We have all experienced the Sympathetic Nervous System’s effects when we have a near-miss accident and feel the palpitations of our strongly beating hearts. Reversely, the Parasympathetic Nervous system is like a brake that slows our heart and breathing after a fright is over, or if the stress is the sort that you can’t get away from. A horse may freeze in response to fright but will often quickly try to run away. However, an abused horse that has learned helplessness in the face of pressure that they can’t escape from will not work with pleasure.

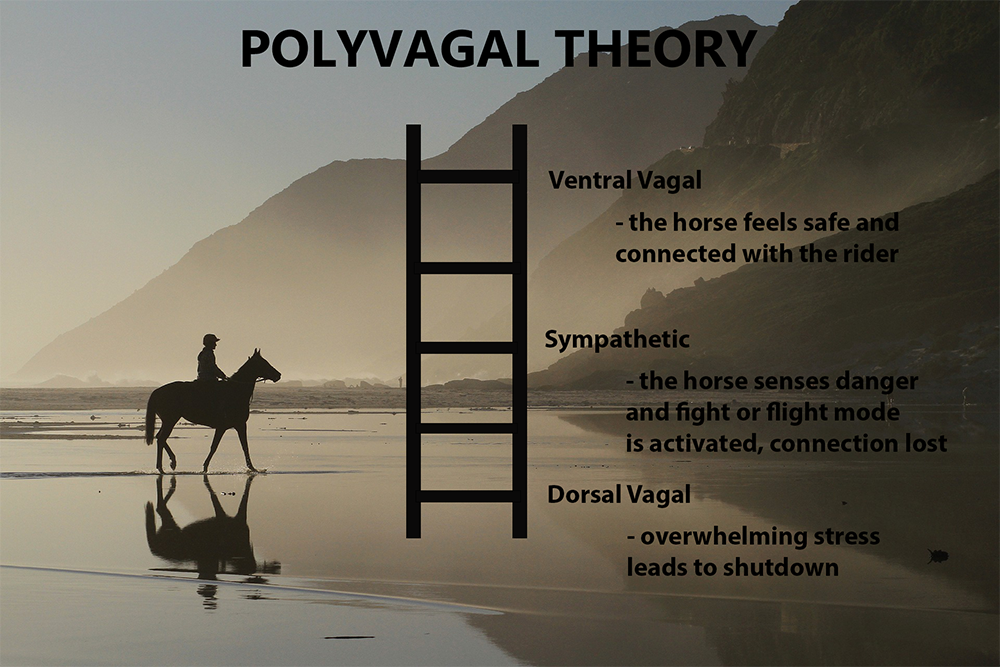

From the point of view of evolution, the Parasympathetic Nervous System is the oldest and most primitive stress response. The Sympathetic Nervous System evolved much later. So there is a hierarchy of stress responses, like a ladder, from the oldest Parasympathetic “Freeze” response to the adrenalin-based Sympathetic “Fight” and “Flight”, then through to the other most recently developed stress response which we call “Cry for Help” or “Connect”. The “Connect” response is also mediated through the Parasympathetic Nervous System but through a much evolutionarily younger branch. Just as technology has improved efficiency and effectiveness as it has evolved, so does our nervous system. The primitive “freeze” response is lifesaving if you are a mouse hiding from an eagle or saving yourself from a cat. But it’s a bit limited as you can’t make any other response than feigning death in that state. Unlike when playing possum, there are a few more options when the adrenalin accelerator is switched on.

“Connect” is a much more flexible and versatile reaction to stress offering many possibilities. Humans in this state can think and feel. Being mammals, horses come into the world with this need to bond and connect as a primary drive. And being a herd animal, they especially have a fine capacity to connect with each other as well as with us.

Parasympathetic “freeze” responses and Sympathetic “fight” and “flight” are activated through the stimulation of the Vagus nerve. The Vagus nerve is the 10th cranial nerve, coming out of the brain and cranium (skull) above the spinal cord. This important nerve is called the Vagus because it wanders over a large part of the body. It is the connection between the brain and the heart. It is also a connection between the brain and the face and vocal apparatus, both of which are involved in expressions and emotion, and therefore with a connection between us.

“They have a fine capacity to connect

with each other as well as with us.”

Dr Stephen Porges has made a substantial understanding of the Autonomic Nervous System when he quite recently identified that there are three types of nerves making up the Vagus nerve. In addition to the Parasympathetic nerve fibres that run at the back (the Dorsal Vagal Complex), the Sympathetic fibres there are more sophisticated myelinated (insulated), and the Parasympathetic fibres which run in the front of our bodies, the Ventral Vagal Complex are responsible for a third instinctive survival response of CONNECT. This is the Social Engagement System which automatically uses the most sophisticated stress response that can be applied. So in fact the fast, evolutionary-recent myelinated, parasympathetic Ventral Vagal System of “connect” will mediate the stress response whenever that is possible. These are the fibres that control some of our social communication, including some facial expression, our larynx (voice box), and pharynx. There are nerve fibres that interact with the nerves that control facial expression and hearing.

So, what does all this mean and what is the significance? What is the importance of this new understanding of these primitive stress responses to us as equestrians?

Ultimately, yes, a horse is a prey animal that uses flight as an important defence. But more importantly, horses are social animals who will automatically respond to low levels of stress by seeking connection. A horse who is feeling safe will also be operating in the Social Engagement System. A horse can feel safe because it is socially engaged. We can potentially learn to be more sensitive to the social communication between us and our horse, and we can be more sensitive in communicating with our horse that we have noticed his communication.

Recent work has shown that horses can communicate with facial expressions, gaze, voice, posture, and behaviour such as pawing. For example, a scale has been developed which helps to identify and quantify a horse’s experience of pain by looking at facial expression. A horse in pain will show similar facial expressions that humans display, for instance, tension around the mouth and lips, and a furrowed brow. Of course, a horse communicates discomfort or nervousness with his face, ears and posture. If we notice his unease and communicate to him that we have noticed it by backing off immediately and repeating the approach slowly, this will help to give him confidence.

“Music has a direct effect on

deep structures in our brains.”

We can help a horse to stay feeling safe in the Ventral Vagal Connection and stay out of adrenaline-driven Sympathetic “fight and flight”, by what we do when we ride and handle them. To do this, we need to stay in our own Dorsal Vagal System – calm and connected. After all, one of the first things a new rider is told is that the horse can tell when the rider is nervous. Keeping the horse connected with us with a sense of safety is not the same as keeping his attention.

For example, if he is a little spooked by the waterfall at Willinga Park I can get his attention by touching him with the whip. Now if I do this very gently with tact, making use of the knowledge that he can easily feel a fly landing on him, then I can keep him connected to me in a way he can still feel safe. But if I use the whip sharply and he feels pain, all the while aware that he is likely to be as sensitive to pain as I am, then I have his attention but I have broken the sense of a safe connection.

I can keep his attention with connection by tactful use of the aids. For example, I can ask him a friendly way to respond to bend. A bent horse is a soft horse. I can ask him just to do tiny transitions within the pace I am in. If I manhandle him back and forwards and be abrupt with my aids, I train the response and get his attention, but I may break the connection if I am not tactful enough. Of course, sometimes it is more important that he is obedient and safe than he is connected. I am not saying that it is wrong to sometimes be very clear and even demanding, but that there are other times where tactfully keeping his attention with connection will help him cope with something that he finds stressful and can stop him from going into a fight or flight state. I must train him at home to really know these subtle aids where he finds it easy to feel safe and connected. Ideally, that is the state he is in when we are doing most of our training.

When he understands it, I can ask a little shoulder in or shoulder-fore in a friendly way so he stays connected even when there is that big red TV screen in the arena at Willinga Park. This is not the same as aggressively bending his head away from the feared object and driving him past it. That is an okay thing to do when it is necessary, but what I am advocating is a different way to think about managing a frightened horse by staying connected in a way he feels safe, and not me just being scarier than the scary thing.

We can use our voice to help him say connected, with soft and slow tones. I like to say “easy, easy” as a general signal that everything is okay. It doesn’t mean stop, or slow. I can use it if he is a little uptight, or when a bicycle goes past, or he makes a mistake, or he is getting confused by something new. Sometimes I will sing or hum to him. Music has a direct effect on deep structures in our brains, so I expect it does on my horse to. Singing will overshadow a noise that is frightening and will give him something to focus on and stay connected. He doesn’t know if I am singing the right words or the right tune. Just choose something calming. Amazing grace is a standby for me.

So, what I am asking is for you to think of your horse’s stress levels like a ladder and try to keep him safely connected with you at the top of the ladder. Notice when he might be going into Sympathetic Fight and Flight and let that cue you to not just get his attention but to bolster that connection he feels with you. Of course, as dressage riders, we use the word connection to also refer to the connection we develop between the bit and the hind leg. The interrelationship between that type of connection and the safe connection is a great topic for another day.

But I hope that if you have taken anything away from this, it is that your connection with your horse is the most important aspect of your riding for you to spend time on. And once you understand the science and instinctive nature behind your horse’s thought processes, the easier it is to build it. The trust and connection that can develop between a rider and a horse can be so powerful that it can make you feel as though you can conquer the world together. And no amount of leaves or flying plastic bags will come between the two of you. EQ