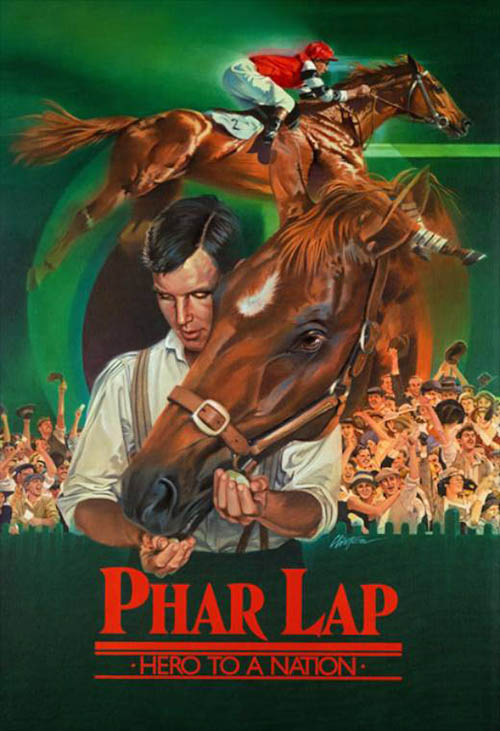

They said there could never be another horse like Phar Lap… until an unwanted hack was found on a remote sheep and cattle station. The 17hh Towering Inferno was destined to play the legendary racehorse in the 1983 hit movie.

“All he ever wanted

to do was gallop.”

Punters will never be able to bet on another horse called Phar Lap. Usually, 20 years must elapse before a dead racehorse’s name may be taken by another, but in the case of Phar Lap, there is a rule which precludes the name ever being used again.

Born in 1926 at Timaru, New Zealand, Phar Lap was sired by Night Raider, an undistinguished stallion, out of Entreaty. Being unfashionably bred, he attracted little sale-ring attention as a yearling and was bought by an Australian for 160 guineas. The chestnut was so big and backward he was gelded. At 15 months he was brought to Australia.

As a two-year-old he won only one race, but in his second season he greatly improved, triumphing 13 times. In 1930 he won the Melbourne Cup over two miles (3,200 metres), and the Futurity Stakes over seven furlongs (1,400 metres) – proving his versatility. Known to his adoring public as “The Red Terror”, he won 36 races before being sent to America to contest the Agua Caliente handicap, which he won easily, adding to his legendary fame. A fortnight later, on 5 April 1932, he was dead. Australia mourned.

There were many theories about how he died: “poisoned by gangsters”, “unknowingly consumed insecticide”, “acute bacterial gastroenteritis”. It took until 2010 for scientists to confirm he was killed by arsenic poisoning – who administered it will never be known.

Jockey Jim Pike had said: “All he ever wanted to do was gallop. It’s a sacrilege really to ride some horses after having been on the back of Phar Lap – there’ll never be another like him.” However, in 1982, Australian producer John Sexton gambled there was another like him; he was going to make a $7 million film about this legendary galloper.

The lookalike didn’t have to run fast but the horse did have to be 17hh, big-boned and preferably a rich red. Phar Lap’s fetlocks were white, and on his thighs were patterns of black spots. Those on the right side took the form of the Southern Cross.

After months of searching, a nine-year-old station hack was found in a paddock at Branga Plains, a sheep and cattle property at Walcha on the NSW Northern Tablelands. The stockmen hadn’t wanted him. His name was Towering Inferno.

“He was just too big for the men to keep getting on and off,” recalls Branga Plains’ Shirley Pye-Macmillan, now in her early 90s. “He was by Yeti, who could be traced back to Rochester Castle, sire of many English Derby winners, out of Chessie, who was descended from the Walers. I kept him because I thought he might one day do something such as become a good three-day-eventer – he was bold with an excellent temperament – we just never got around to trying him out.”

After being purchased by the production company he was insured for many millions of dollars. He immediately became “Bobby”, the stable name given to the original by his strapper, Tommy Woodcock, and work began to prepare him for the silver screen.

“There’ll never be

another like him.”

Movie horse trainer, Heath Harris, and his wife at that time, Evanne, headed the team which was to educate this equine star, acclimatise him to the outside world (he’d never been out of Walcha), source and school other horses to double for him, train movie actors to ride like jockeys and instruct jockeys how to ride in movies.

Phar Lap used to tear shirts off the backs of stable boys, so Bobby had to learn to do it too. He had to work at liberty, come when he was called – even in a 40,000-hectare paddock –gallop freely beside a camera mounted on a tracking vehicle and, on cue, rear, strike, paw, nod, look left and right and play dead.

Much of his training took place at the old Sydney Showground, now the Centennial Park complex. Steve Gladstone, who still works at these stables, remembers when he first saw the big horse with trainer Harris: “I’d seen plenty of good horsemen but I felt this bloke was outstanding; I’d never before seen anyone work a horse with lungeing whips like he did.”

Whenever possible he would watch these schooling sessions and one day was asked to audition, resulting in his getting a job as a jockey, and as a wrangler at many of the film’s locations. He rode a chestnut “extra” in the memorable sand dune sequences (filmed at Cronulla) doubling for Martin Vaughan who played Phar Lap’s trainer, Harry Telford.

Steve Gladstone also rode in trackwork and racing scenes. “I remember producer Sexton saying to the late Roy Higgins, who was the picture’s consultant, that he wanted the horses to race and finish in a particular order. ‘Any trouble with that?’ he had asked. ‘Oh no, we do it all the time!’ replied Roy.” (Higgins won almost every major race on the Australian calendar and retired in 1983).

“All the good jockeys rode in this film, such as Neville Boyle and Peter Cuddihy… I can’t remember all their names but there were heaps of them,” says Gladstone. “When their scenes were finished an assistant said she’d take them to an office where they’d be paid. They didn’t know they were getting any money! They had just wanted to be in the Phar Lap movie – they idolised the horse.”

One of the film’s many challenges was finding a location that mirrored the American racetrack on which The Red Terror ran his last race in 1932. “American tracks aren’t turf, they’re dirt,” says director Simon Wincer, “but we somehow managed to find this little country track high up in the Snowy Mountains in Adaminaby and, thankfully, we obtained permission to plough the turf up and make it like the US style. “We erected a huge, old-style grandstand and incredibly the surrounding landscape was a great double of the Tijuana course where the original race had been.”

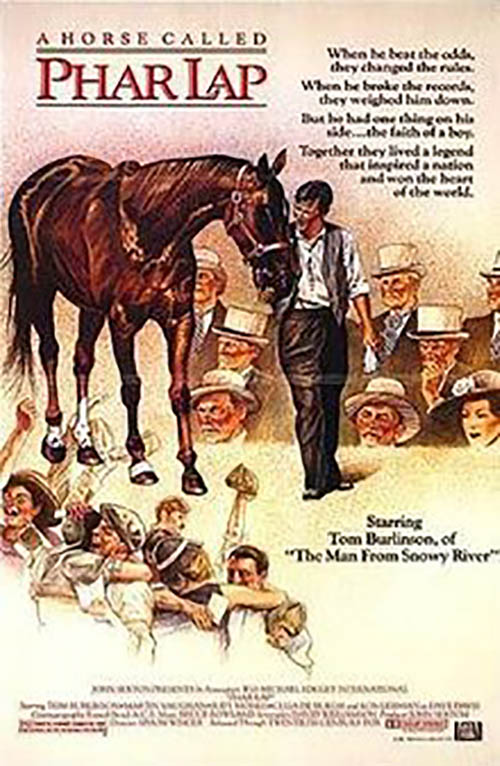

Other challenges were experienced by some of the film’s key players – notably James Steele (jockey Jim Pike) and Tom Burlinson (strapper Tommy Woodcock). Firstly, Steele had to lose 9.5kg – and learn to ride. “I got the part because I’m 5’5” (170cm) and looked like the jockey,” he told this writer when she interviewed him after the movie’s release. “When the racetrack sequences were being shot, many elderly people who were watching the filming would come up and talk to me as if I was the real thing.”

On the first day of his crash course in horsemanship he was shown a couple of stables where strappers were mucking out, grooming and picking out hooves. He thought all that looked easy enough. “The next day Heath Harris opened another door and simply said: ‘James, meet Towering Inferno – I’ll be back in an hour’, shut the door and went away.

“I was all alone with the animal,” says Steele. “He knew he was big, he knew he was a star and he knew I was scared of him.” Controlling a desire to scream for help, climb over the door and give up acting forever, Steele began cleaning the stable.

“But Bobby wouldn’t move out of the way. I kept saying ‘excuse me’ and gently prodding him but he just looked down his huge nose at me. Then I realised I had to pretend I was the boss and he seemed to believe me – thank God!”

“All the good jockeys

rode in this film.”

Riding lessons in short stirrups were the actor’s next hurdle and Steele went into jockey mode straight away. He only had a couple of bingles. “Because I’m a performing clown as well as a straight actor, I didn’t get hurt because I knew how to fall. The real jockeys on the set were very good to me. I think they were quite impressed that an idiot actor was having a go.”

As the film progressed, he established a successful riding rapport with the big horse; but the actor who really had to know Bobby was Tom Burlinson. He’d become a very capable horseman when starring in The Man From Snowy River the year before; now, he had to dramatically change his style and, most importantly, he had to relate to the horse from the ground.

“Having read about the character of the famous strapper, I felt the most important thing about playing him wasn’t his relationship with his trainer, or even his wife – but with his horse,” says Burlinson.

When Woodcock, who died in 1985, was first introduced to Towering Inferno, the big horse had been in rehearsal for some time and was becoming accustomed to cameras, crews and clapper boards. But, unlike the original Phar Lap, he would not eat sugar lumps.

“So we had to use pieces of apple which would quickly turn brown and mushy in Tom’s hand,” Harris recalls.

On the day of the introduction, the kindly old man had walked towards the stable. The horse looked over the door and then stood at the back of the stall. “Hey Bobby,” called Woodcock, offering him one of the sugar lumps he always carried in his pocket. Towering Inferno looked over the door again and took the sugar – the first lump he had ever eaten. From that moment he never refused them from anyone.

At this initial meeting Woodcock had thought the horse was a passable lookalike, ‘but I bet he hasn’t got the Southern Cross on him’. Harris pulled back the rug revealing the identical markings. “Then I reckon he’ll play the part all right,” murmured the gentle horseman who, back in the thirties, had developed a unique affinity with Australia’s most famous galloper. They were always in each other’s company and often slept and ate their meals together. When the horse had died in his arms, the 27-year-old strapper had sobbed uncontrollably. Phar Lap was only five and the third-highest stakes-winner in the world.

The Australian version of the film starts with the death then continues with a series of flashbacks; in the US, with the title A Horse Called Phar Lap, it opens in a more traditional way with his arriving from New Zealand and being unloaded from a ship. Dying at the end made it more dramatic since American residents were unfamiliar with the Phar Lap story.

Burlinson says it’s one of the best films in which he’s appeared. “And, personally, I think the American cut is more powerful.”

Both versions generally received positive reviews. The New York Times found it an “inspiration”, dubbing it “Rocky with Hooves”. And it did very well at the Australian box office. One reviewer commented: “It’s buoyed by good performances, strong production values and David Williamson’s writing, which finds a genuine but bittersweet way to commemorate one of Australian sport’s best performing athletes.”

“Burlinson says it’s

one of the best films in

which he’s appeared.”

“I thought Bobby would forget me after filming finished,” says Burlinson, “but eight months later at a press conference he reacted to me after 30 seconds. He did all his stuff like hanging his head in my lap and other things which we’d done together almost a year before. He didn’t come on the promotional tour around America but I had to sign on his behalf for people wanting his autograph for their horses. Bobby was very special.”

(The actor made another racing picture years later, also directed by Simon Wincer. He played Dave Phillips, trainer Dermot Weld’s foreman, in The Cup about Damien Oliver’s victory in the 2002 Melbourne Cup).

Towering Inferno retired from filming but retained a high profile working for various charities. He was living at Heath Harris’s Mt White property on the NSW Central Coast when tragedy struck during a violent hailstorm in April 1999.

The 26-year-old was discovered by Harris, who was forced to put him down after he was struck by lightning. His former trainer was gutted. “I’ve lost a good mate,” he told reporters. “He thrived on his work and was a true performer with incredible stamina. I reckon his heart was almost as big as Phar Lap’s.”

Ironically, Phar Lap means “lightning” in Sinhalese. EQ

Next month in our series on horses and movies, we look at Hidalgo, starring actor and horse welfare activist Viggo Mortensen.

You also might like to read by Suzy Jarratt:

Black Beauty Rides Again – Equestrian Life, January 2021

The Secrets Behind ‘Australia’ – Equestrian Life, December 2020

From Roy Rogers to Saddle Clubbing, the Horses Starred – Equestrian Life, November 2020

Poetry Jumps to Life & Yes, Horse Can Talk! – Equestrian Life, October 2020

When Your Co-Stars Are Real Animals – Equestrian Life, September 2020

Horsing Around on the Big Screen – Equestrian Life, August 2020