Osteochondromas are abnormal bony growths that develop towards the end of a bone, generally in the vicinity of a growth plate. They are benign tumours that can occur in multiple species of animals and humans, and although they can become malignant in some species (dogs and humans), osteochondromas have not shown any cancerous transformation in horses.

These bone growths are more commonly seen in the horse in the distal caudal (lower, hind) aspect of the radius, which is the bone above the carpus or knee, but have also been diagnosed on the front of the radius, on the tibia or long bone above the hock, the calcaneus bone at the back of the hock, the upper pastern in Tbourida horses and the nasal bone.

Osteochondromas differ from other bony growths known as exostosis in their histological make-up, with osteochondromas having a cartilage cap, which is a remnant of cartilage that would normally undergo endochondral ossification to form bone. An osteochondroma will also show evidence of a bone medullary (inner core) and a cortical (outer) structure, whereas normal bone exostoses such as splints and ringbone have no cartilage and develop simply as an extension of the bone cortex. It is thought that osteochondromas are developmental rather than neoplastic in origin and occur because a small area of the cartilage in a growth plate region becomes displaced during the normal growth phase and develops into a separate area of bone growth, above the original growth plate.

Instead of the cartilage tissue completely ossifying and becoming incorporated into the shaft of the bone, this island of tissue continues to multiply and produce more cartilage that ossifies as a discrete lump and results in the formation of a tumour. These osteochondromas also differ from the small exostoses seen at the back of the distal radius that are remnants of the growth plate and remain as small spikes of bone on the physis or growth plate when the horse matures.

SECONDARY EFFECTS

Whilst osteochondromas may not be painful as they develop, they can be cosmetically unsightly and often cause secondary effects to surrounding tissues as they grow, and it is this resulting damage and pain in the adjacent soft tissue that compels the owner to seek veterinary advice.

Osteochondromas on the back of the radius are frequently diagnosed after they have grown big enough to put pressure on the soft tissue structures that run down behind the knee, particularly the deep digital flexor tendon, causing inflammation that can progress to a tear in the tendon. The typical clinical presentation of an osteochondroma on the caudal radius is swelling in the carpal tendon sheath, seen as swelling on the outside of the lower forearm and on the inside and outside aspects of the upper cannon. Sometimes, there is no pain elicited when the sheath is palpated, but typically the horse resents flexion of the knee, either as a response to the increased pressure in the sheath or the pain of the osteochondroma pressing on the tendon.

Horses showing lameness can vary in severity from a mild 1/5 lameness to a more severe 4/5 lameness, depending on the degree of tearing and the horse’s individual pain tolerance. Affected horses will often trot with the affected limb abducted away from the body.

Osteochondromas located in other sites will produce clinical symptoms relating to the structures they impinge upon, for instance, an osteochondroma on the front of the radius can cause swelling in the carpi radialis sheath. The osteochondromas seen on the dorsal, proximal first phalanx (front of the top of the pastern, immediately below the fetlock joint) in Tbourida horses, cause damage to the tendons that pass in the vicinity (the common and lateral digital extensor tendons) and secondary damage to the fetlock joint and lower cannon bone. The clinical presentation of an osteochondroma compared to that of a physeal remnant exostosis are very similar, however, osteochondromas are more commonly diagnosed in young horses (2-4 years old) whereas the physeal remnant exostosis may be detected in older horses (average age 6 years) as osteochondromas tend to stop growing when the horse matures and stops growing.

DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES

Osteochondromas located above the knee are readily identified on X-ray, however, those located in more unusual locations may require more diagnostic procedures to be conducted to confirm that they are an osteochondroma and not an exostosis from other origins. Osteochondromas are usually located 2-4cm above the radial growth plate and need to be differentiated from the remnant exostoses that are often closer to the end of the bone (closer to the growth plate) or not clearly identifiable on X-ray.

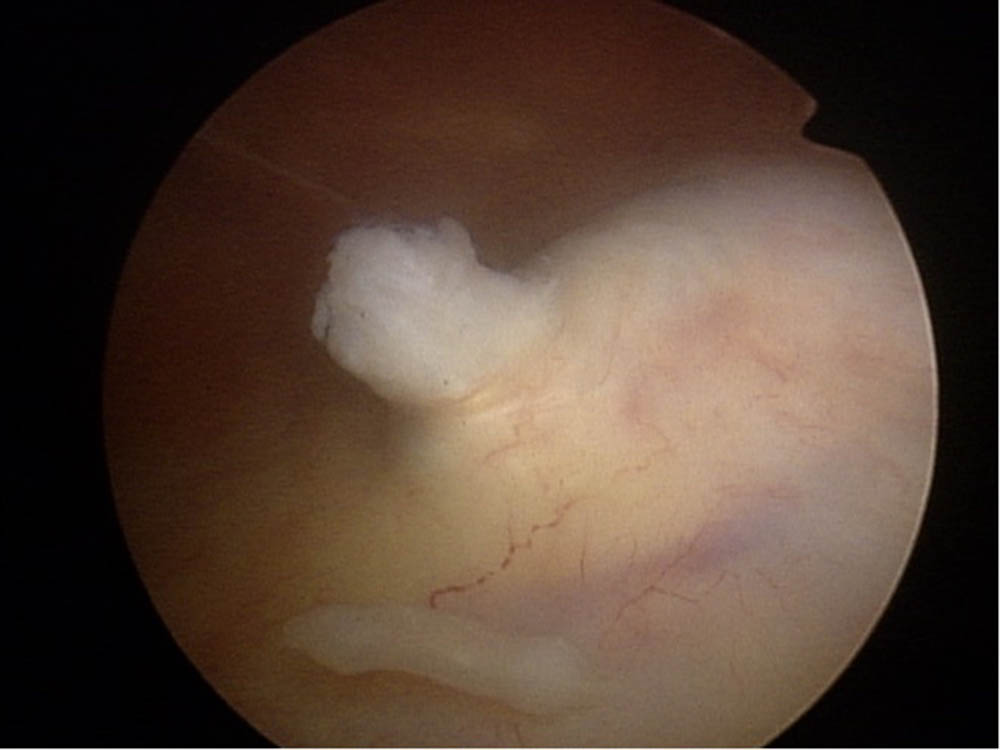

Ultrasonography can be used to assess the soft tissue structures within the carpal sheath or at other sites to identify secondary areas of damage, but does not give as much information about the osteochondroma as an X-ray does. Using an MRI or a CT scan can provide a lot of information about the bone and cartilage in the osteochondroma, but the physical limitations of these devices to assess horse limbs above the knees and hocks reduce its frequency and suitability to assess most osteochondromas. An MRI or CT scan can be useful for those osteochondromas that are positioned in more atypical sites, such as the pastern or nasal bones previously noted above. Treatment of choice for an osteochondroma is the surgical removal of the bone, and this is usually achieved via a tenoscopy if the bone is located within a tendon sheath. A tenoscopy is performed using an arthroscope to access the osteochondroma through a small incision in the tendon sheath, and this allows the surgeon to remove the bony growth and debride any frayed tendinous tissue that has occurred. By utilising the arthroscope through this keyhole approach, the recovery time is a lot shorter than it would be if the sheath was opened fully to remove the lesion.

Osteochondromas do not regrow or recur once removed if they are removed completely at the time of the initial surgery. As with any surgery involving tendons within a sheath, the formation of adhesions or the risk of infection in the sheath following surgery cannot be discounted and good aftercare is vital to minimise these complications. Osteochondromas in atypical locations can be removed by an open surgical procedure provided the tumour is accessible and can be removed without damaging vital tissues.

Prognosis following removal is generally excellent unless there has been major damage to the secondary structures, such as a torn tendon, in which case the healing of these tissues becomes the limiting factor in the horse’s full recovery. EQ

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE TO READ THE FOLLOWING BY DR MAXINE BRAIN:

Don’t Forget the Water – Equestrian Life, January, 2022

Understanding Anaesthesia – Equestrian Life, December, 2021

A Quick Guide to Castration – Equestrian Life, November, 2021

Caring for Mammary Glands – Equestrian Life, October, 2021

Sepsis In Foals – Equestrian Life, September 2021

Understanding Tendon Sheath Inflammation – Equestrian Life, August 2021

The Mystery of Equine Shivers – Equestrian Life, July 2021

Heads up for the Big Chill – Equestrian Life, June 2021

The Ridden Horse Pain Ethogram – Equestrian Life, May 2021

The Benefits of Genetic Testing – Equestrian Life, April 2021

Heavy Metal Toxicities – Equestrian Life, March 2021

Euthanasia, the Toughest Decision – Equestrian Life, February 2021

How to Beat Heat Stress – Equestrian Life, January 2021

Medicinal Cannabis for Horses – Equestrian Life, December 2020

Foal Diarrhoea Part 2: Infectious Diarrhoea – Equestrian Life, November 2020

Foal Diarrhoea (Don’t Panic!) – Equestrian Life, October 2020

Urticaria Calls For Detective Work – Equestrian Life, September 2020

Winter’s Scourge, The Foot Abscess – Equestrian Life, August 2020

Core Strengthening & Balance Exercises – Equestrian Life, July 2020

The Principles of Rehabilitation – Equestrian Life, June 2020

When is Old, Too Old? – Equestrian Life, May 2020